The strict time constraints of the collodion process meant that the photographer needed to assume a near-professional approach to the task at hand. The photographer needed to be able to bring all the required chemistry on-site and required either a permanent studio or transportable darkroom facility to prepare and develop his plates. For photography to gain wider popularity a less demanding process was required.

Slow drying plates

In early attempts to create a dry-plate process photographers used a variety of substances to keep the collodion plate moist for longer periods and extend the working time of the photographic plate. George Shadbolt developed the honey process (honey diluted in distilled water) in 1854, where sugar in the solution kept the collodion moist. This sugar-based concept evolved in further experiments with sweet wort, glycerin, raspberry vinegar, and finally in the Oxymel process. In 1856, John Dillwyn Llewelyn (1810-82) used Oxymel (a medical tonic of honey and vinegar) to keep sensitized collodion moist for months, albeit at the expense of reduced light sensitivity.

In 1855 Jean Marie Taupenot (1824-56) published details of a process using sensitised layers of both albumen and collodion. The collodion-albumen plate was very slow, but capable of fine resolution and could be kept for weeks before exposing. By making an ’emulsion’ of silver bromide in collodion, and coating the mixture on a glass plate, William Blanchard Bolton (1848-99) and Benjamin Jones Sayce (1837-95) found in 1864 that the dried plates could be kept for long periods before exposure without loss of quality. Like all dry-collodion processes the collodio-bromide plates were less sensitive than the wet process but despite the loss in sensitivity, the convenience of previously prepared and stored plates held great appeal for photographers. A small British industry developed in manufacturing and delivering collodion dry plates and from 1867 The Liverpool Dry Plate and Photographic Printing Company sold precoated plates made by this process.

Limitations of mid-nineteenth-century transportation did however have a greater impact on dry plate success than the actual technical performance of the plates. The time it took for dry plates to be delivered from British factories to New York City was so long that the plates had lost useful light sensitivity – they were better suited as window panes than photographic plates. Further discouraging the use of European-made dry plates, the imported plates were also heavily taxed in the United States due to import tariffs on glass designed to protect the domestic glass manufacturing industry.

Gelatin Dry Plates

The first account of a really satisfactory dry plate process was published by Richard Leach Maddox (1816-1902). An enthusiastic photographic experimenter, he found that the ether vapour of the wet-collodion process affected his poor health and he searched for a substitute for collodion. He turned to gelatin, a substance that had been employed before in photography, notably as a sizing agent used in the preparation of papers suitable for the Calotype process. Attempts had been made to use it as a direct substitute for collodion but with no success. Maddox found that by mixing cadmium bromide and silver nitrate in a warmed solution of gelatin an emulsion of silver bromide was formed in the gelatin. Coated on glass plates and dried, this sensitive material retained its properties for some time after manufacture. The process was published by Maddox in The British Journal of Photography on 8 September 1871. As first described, the process was imperfect but it attracted the attention of other experimenters. This new dry plate technology also offered more than just a long storage life - the gelatin plates were about 60 times more light-sensitive than collodion plates. Like Archer before him, Maddox did not choose to patent protect his discovery and invention, instead sharing the knowledge of the gelatin dry plate process freely with the growing photographic community.

In 1873 John Burgess advertised ready-mixed and bottled gelatin emulsion for sale based on Maddox’s formula, for coating by the photographer. It was not very successful and Burgess did better with ready-coated dry plates, which he sold from August 1873. These early gelatin dry plates were less sensitive than wet collodion and offered no great advantage.

In 1874 an amateur photographer, Richard Kennett sold a dried gelatin emulsion which he called ‘pellicle’, to be reconstituted with water before coating by the user. In the preparation of the ‘pellicle’, it was dried by heat and, unknown to Kennett, this was responsible for a great increase in sensitivity which was observed in the coated plates. Charles Bennett of London investigated the effect and on 29 March 1878, he published in The British Journal of Photography details of a new gelatin dry-plate process. The prepared gelatin emulsion was ‘ripened’ by prolonged heating, producing a considerable increase in the speed of the emulsion. Bennett’s discovery was a major breakthrough - the new dry plates were easily manufactured, very sensitive, and retained their properties for long periods. Exposure times could be reduced to as little as one tenth of those necessary for wet-collodion plates.

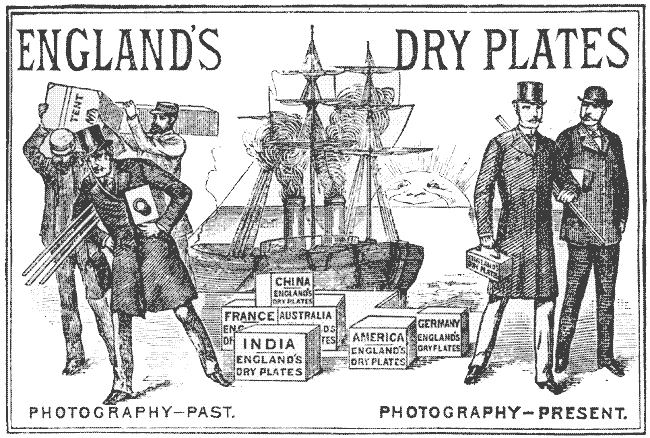

For the first time, an entirely satisfactory process permitted the manufacture of dry plates for sale. Within months the new plates were being produced by many manufacturers. Among the first in England were Wratten and Wainwright of Croydon, Mawson and Swan of Newcastle and Samuel Fry of Kingston upon Thames. Within a few years, the wet-plate process had been discarded by all but a few diehard photographers (although it remained in use in the printing industry until more recently). Now the photographer no longer needed to carry a dark tent and chest of chemicals when on an excursion; a camera, tripod and a few loaded plateholders were all that was required. The dry plates, bought from a manufacturer as required, were exposed in the field and processed in the darkroom on the photographer’s return.

The new process brought about other changes in photography. When the photographer prepared his own materials each had his own methods and formulae. Depending upon the method of preparation the exposure for the wet plate would vary. Since the plate was developed on the spot any errors of exposure could be immediately seen and corrected during development, or the photograph could be repeated. The gelatin dry plate, however, could be manufactured in quantity with consistent characteristics. It was therefore necessary to devise methods of measuring and describing the sensitivity of the plate for the benefit of the photographer. The science of Sensitometry, as it is called, was pioneered by Ferdinand Hurter and Vero Driffield in England during the last 20 years of the 19th century. The ‘H&D’ scale of plate sensitivity remained the standard method of speed determination for a long time.

The manufacture of plates of known and constant sensitivity made it possible and desirable to develop methods of exposure calculation and measurement. One of the most efficient early calculators was the Actinograph, invented by Hurter and Driffield, and sold from 1888. Having assessed the prevailing lighting conditions, the photographer was able to compute with the calculator the necessary lens aperture and exposure time. The first exposure meters were actinometers, which enabled the photographer to measure the brightness of the light available. They were usually made in the form of a pocket watch, and carried a piece of printing out paper which darkened when exposed to light. The time taken for the paper to darken to match a standard tint was measured, and by applying this information to a calculator the necessary exposure details could be worked out. One of the first actinometers was sold by Stanley of London around 1886, but the most popular English models were the ‘Infallible’ actinometer made by Wynne, and the later Watkin’s Bee meter, first sold around 1900 and in general use until the 1930s.

Most importantly with the introduction of the gelatin dry plate, there was a huge reduction in exposure times. For the first time ‘instantaneous’ photographs, with exposure times at a fraction of a second, could be achieved without difficulty. The photography of moving subjects was at last possible.

George Eastman

Within ten years of Maddox’s introduction of the gelatin dry plate, they were being commonly produced in factories and distributed widely. Their ease of use and their ready availability expanded the circle of active photographers, prompting a large increase in amateur participation. In 1877, one of these newcomers, 24-year-old George Eastman, of Rochester, New York, started experimenting in his mother’s kitchen. He learned to make his own gelatin dry plates, based on the writings of the British innovators, including Bennett. By 1878 he had not only refined his process, but he had invented a machine to mass–produce dry plates.

Later in 1878, while still working as a bank clerk, Eastman travelled to England to solicit commercial interest in his as-yet unpatented dry plate machine. There Eastman was introduced to Charles Fry and his partner, Charles Bennett, the same man whose earlier writings had inspired his own work. Eastman quickly realized that these innovators of dry plate technology were unable to meet the demands for dry plates using the current state-of-the-art equipment, so he returned to the U.S. and applied for a patent on his dry plate coating machine in 1879. In 1880 he began commercial production of dry plates in a rented loft in Rochester, and in 1881, with demand for dry plates soaring, he left his job with the bank to open the Eastman Dry Plate Company as a full-time venture. In 1883 the Eastman Dry Plate Company moved to the current site of Kodak headquarters, and within a year Eastman would begin experimenting with a new carrier for photographic emulsion – celluloid film.